|

|

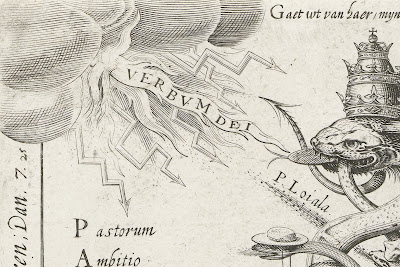

Berruguete, late 15th century (crop)

|

Our understanding of what happened more than seven hundred years ago

is based on little evidence. Much of it is assumption and

interpretation, in line with traditions of scholarship. For ages,

religious institutions decided what manuscripts were worth and

permissible to be saved and made public. There will still be

treasures hidden in private collections or forgotten archives. One

and a half century back, this will have been more true than today.

In

1867, a manuscript surfaced in the Netherlands. It seemed to be a

13th century copy of an older original, in unusual lettering and

containing laws and histories from an era before our year zero. Its

contents puzzled the few who got to see it. Was this too good to be

true? Or would it have been recognized as a potential threat to the

then monarchist-protestant state?

Five

years later, the first translation was published as "Thet Oera

Linda bok", named after the Oera Linda clan that seemed to have

initiated the manuscript and preserved it through the ages. Even before

publication, the verdict had already been pronounced in newspapers

and magazines: it had to be fake and anyone who thought otherwise was

a fool. In 1876, the first and only 'evidence' against authenticity

was presented: it could not be authentic, because its language would

be 'gibberish'. However, some of the most prominent Old Frisian

specialists judged very differently.

In 1938, the controversial manuscript was donated to the Frisian

provincial library by the then owner, Cornelis Over de Linden IV

(1883-1958), who trusted that his donation would finally lead to

proper study of the document and its contents. Until today, this

never happened. The library states that it is “commonly

believed to be a forgery”,(*) but substantiation of this belief is

hard to find. The main ‘evidence’ seems to be the fact that

scholars do not take it seriously... Asking the question if the

manuscript or its contents could be authentic after all seems to have

been taboo in Dutch academia since the late 1870s.

On December 14, 2020, the Oera Linda Foundation was registered, with

the purpose to promote research on, translations of, and publications

about the manuscript (or codex) known as the Oera Linda-book. The

document begins with a letter of instruction, dated 1255 AD by the

last known copyist of the writings, Hidde Oera Linda, who briefed his

son Okke to also make a copy “so that they will never be lost”.

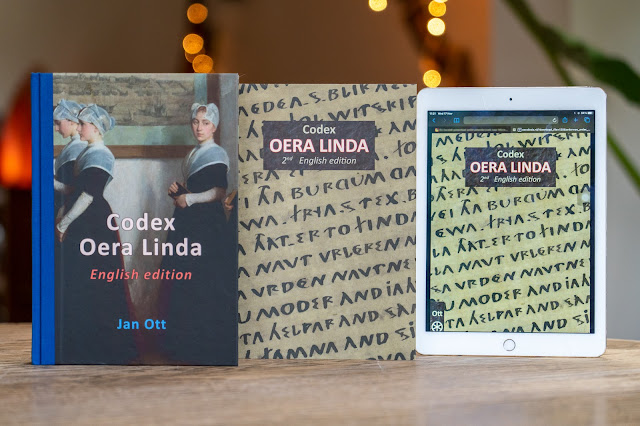

The foundation's first publication, 'Codex Oera Linda', is intended

to be the modern version of such a new copy. It contains a new

transliteration and an English translation of the original texts,

with an index of proper names and a suggested alternative reading order. It can finally replace the only English edition thus far from

1876 by William Sandbach, which was a translation of the first (1872)

Dutch translation by Dr. Jan Ottema and which included a mutilated,

so-called facsimile print of the pages with the wheel-based letters

and numbers.

In our times, ever more people learn to make up their own minds about

issues relevant to them. For those interested in our deepest roots,

the origin of our language and consciousness — in particular our

innate desire for freedom, truth and justice — Codex Oera Linda may

provide a wealth of inspiration.

(* Dutch: "Binnen enkele jaren was de algemene opvatting dat het om een vervalsing ging" http://oeralindaboek.nl/; click on "over het Oeralindaboek")